Last month millions of households across England, Wales and Northern Ireland filled in their census returns, which among other things, asked householders whether they shared a home with someone ‘Unrelated, including foster child’.

Demographic evidence such as the census allows governments to make informed decisions about how resources are spent in the present, but they are also vital for historians investigating the diversity of family life in the past, including the experience of Care Experienced children and young people.

The first statutory national census was taken in 1841, but the question of how members of the household were related to each other was not asked until 1851. Even then, census enumerators often did not record relationships in detail. Young children were usually recorded simply as ‘son’ or ‘daur’ (meaning daughter), when they were actually step-children, grandchildren, other kin, or children who were not related by blood to those who cared for them. Historian Eleanor Page’s study of the parish of Ancoats in Manchester found one example of William Hamilton, who was born in 1854. William was illegitimate, and when his mother Ellen died when he was still a baby, he lived with his grandmother Ann. In the 1861 census he is listed as Ann’s ‘son’, and the circumstances of their relationship only become clear by cross-referencing the census with birth and death certificates. Historian Deborah Cohen has suggested that illegitimate children in the nineteenth and twentieth-centuries were commonly brought up as their grandparent’s child in order to hide the stigma associated with illegitimacy at the time, but from the census it is unclear whether William’s identity was deliberately hidden by his family, or whether it was a mistake made by the enumerator. We also cannot know how William perceived his own identity, and whether he knew about his birth status as he grew up.

Occasionally, the term ‘nurse-child’ comes up. This referred to an infant taken care of by a paid carer in their home, in an arrangement more similar to fostering today. However, there was no official definition of these relationships, or guidance on how they should be recorded. It was often up to the household and the individual census enumerator to decide how much detail they provided for that child’s identity. The 1911 census was a watershed for historians in terms of the detail of questions asked about marriage and fertility. For the first time, couples were asked how long they had been married, how many children had been born to them, and how many had died. Historians can use this information to track down children ‘missing’ from their biological parents’ household, and to understand the blended nature of families formed by death and subsequent remarriage.

Historians’ understanding of how many Care Experienced children there were in nineteenth-century Britain and how they understood their identity or relationship to those who cared for them is limited, partly because of these murky definitions. There are other issues, too. Care work often does not appear as an occupation in historical censuses, for example. Historians such as Jane Humphries and Carmen Sarasúa have highlighted that this causes problems for how we measure the economic value of women’s work in particular, but it also means that we lack statistics on who was required to care for vulnerable children, and how that care was seen by the society around them. The census was also taken only every ten years. This means that evidence of informal or short-term care too-often slips through the gaps. Researchers could find a child born in 1840 in the 1851 census at the age of 11, for example, but are left with very little information of their experience in their early childhood.

When it comes to trying to investigate the experience of Care Experienced people in the past, the census is a gift, but it is also imperfect. The questions asked in 1851, and in 2021, tend to define ‘relatedness’ in terms of blood or law. A biological or marital relationship is prioritized, and there is little interrogation of exactly who has responsibility towards children in their care and how this is understood. A biological or legal ‘parent’ may not be willing or able to care for children, and the most significant adult in a child’s life may not be a person who is related to them in a straightforward way. This was particularly the case in informal care relationships before the development of legal adoption in the 1920s. As historian Katie Barclay has noted, acceptance of responsibility to feed, clothe and house a child might not necessarily mean that a child was loved and accepted as a member of the family. The quality of these relationships beyond these more basic obligations is much harder to get at in sources such as the census. The term ‘unrelated’ to refer to a foster child in the 2021 census is legally correct, but it does little to encompass the range of emotional relationships involved in fostering and care.

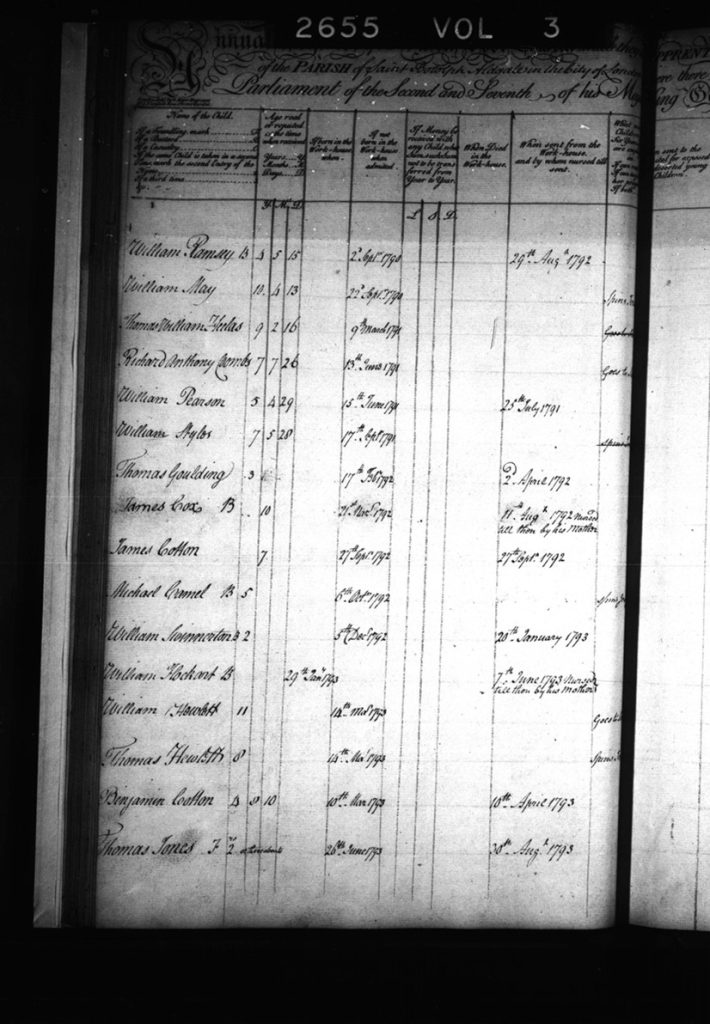

Historians try to get around these issues by finding as much information as possible about families from a range of sources, but this becomes more difficult the further back in time you go. Care Experienced children and young people might appear in the records of institutions such as state and charitable children’s homes. The archive of the London Foundling Hospital (founded in 1741) contains thousands of records, meticulously detailing the early lives of their charges, and their movement from the hospital to nurses and foster families. Children whose families applied for poor relief appear in the accounts and letters of poor law officials, who could arrange for those without parental care to be nursed at parish expense. This document, digitized by the London Lives project, is a ‘Register of Poor Children’ under 14 years of age in the care of the London parish of St Botolph Aldgate in 1794. The register records the name of the child, marked by an F, B or C (standing for ‘Foundling’, ‘Bastard’ or ‘Casualty’), their age, whether they were born in the workhouse, and whether they could read or say their prayers. Crucially, the register also records ‘If discharged from the Parish to whom delivered, and where living’ as well as the name of their nurse.

Some families left autobiographies, letters and diaries. We have more and more examples written by ordinary people from the late eighteenth century onwards, helped by a growing literacy rate and the improved survival of these documents in archives and passed down by families. Historians such as Emma Griffin have used these life stories to examine working-class childhoods, which were often punctuated by a mixture of paid, kinship and community care. Life stories show that care could keep families going through parental death, unemployment and poverty, and detail the range of experiences of care. Some children found loving homes, while others experienced exploitation and abuse. These shades of experience are hidden in censuses. A census return can therefore provide an anchor, around which historians can weave other types of sources. Slowly, we can build up a picture of the lives and experiences of children in the past and those who cared for them.

Further Reading:

‘A Guide to Census Records’, The National Archives [https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/help-with-your-research/research-guides/census-records/#5-people-in-the-census]

Katie Barclay, ‘Love, Care and the Illegitimate Child in Eighteenth-Century Scotland’, Transactions of the Royal Historical Society 29 (2019)

Deborah Cohen, Family Secrets: The Things We Tried to Hide, (London: Penguin Books, 2013)

Emma Griffin, Breadwinner: An Intimate History of the Victorian Economy (New Haven, Yale University Press, 2020)

Jane Humphries and Carmen Sarasúa, ‘Off the Record: Reconstructing Women’s Labor Force Participation in the European Past’, Feminist Economics xviii (2012)

Eleanor Page, ‘Unwed Mothers and Illegitimacy in Industrial Manchester, 1840-1870’, unpublished BA dissertation, University of Manchester, 2021

Ian White, ‘Very Near the Truth: A Brief History of the Census in Scotland’, in Scotland’s Population 2009: The Registrar General’s Annual Review of Demographic Trends (2010), [https://www.nrscotland.gov.uk/files/statistics/annual-review-09/j1201512.htm]