Equipped to house up to 400 boys, the ship was launched as part of a broader movement to establish industrial schools for poor, vagrant and destitute children in Britain.

The first boy to unofficially board the Mars when it was launched in October 1869 was inspired by the possibilities of imperial adventures. As noted above, the first boy was Murdoch McLeod, the adventurous bookbinder’s apprentice, who had been inspired by the novel Swiss Family Robinson to ‘run away to sea’.

Two years later, though, Murdoch attempted to escape, by taking a life-buoy and swimming through the night to Tayport, where he was found and returned by a police office. Much later in life, McLeod was interviewed about his time on the Mars, and recounted how he was ‘slung across cannon’ and ‘lashed with a rope’s end’ as a boy.

In contrast to the volunteer McLeod, the first boy officially registered was David Petrie, who had been charged under section 14 of the 1866 Industrial Schools Act with being Destitute and Homeless. His mother’s address was listed as Dron’s Close, his father’s whereabouts were unknown. In theory, industrial schools like the Mars were meant to house and educate the poor, as distinct from the reformatory school for children convicted of crimes. In practice, children were sentenced to time in an industrial school by magistrates for things like begging, to being in the company of reputed thieves. For the children, the experience would have been difficult to distinguish from a criminal proceeding.

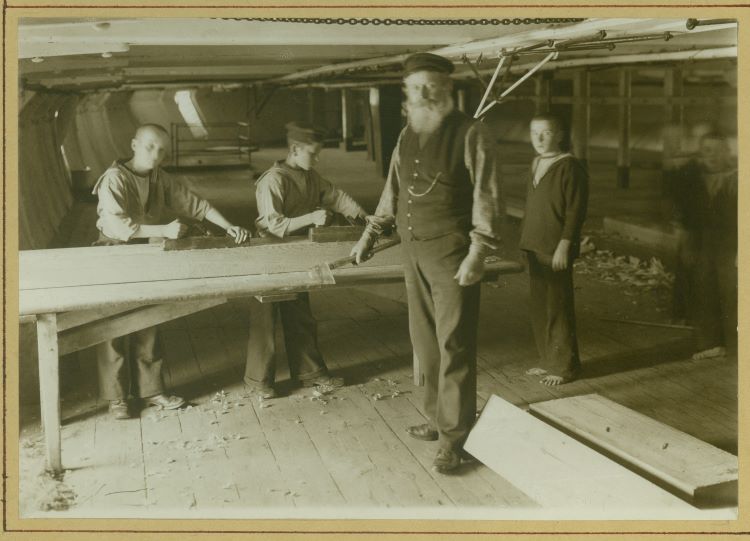

On arrival on the ship, the similarity to a prison continued. Children were first stripped and examined by a medical officer. Their hair was cut close to the scalp. Then they were bathed and given a uniform to wear. Their names and details of their families and ‘sentence’ were noted in a log-book. In a practice very much drawn from prison camp life, each child was assigned a number which replaced their name. From that point on, even just amongst the children themselves, they were only referred to by their assigned number.

Efforts to strip away individual identity from the boys were part of their training for a life at sea, but also greatly reinforced the effects of removal from their homes. Boys were deliberately given little opportunity to maintain connections with family and friends. Parents could apply for discharge of their children but were almost always refused. The notes accompanying one of the very few successful applications for discharge in 1888 emphasised that the committee ‘did not wish to encourage applications of this nature’.

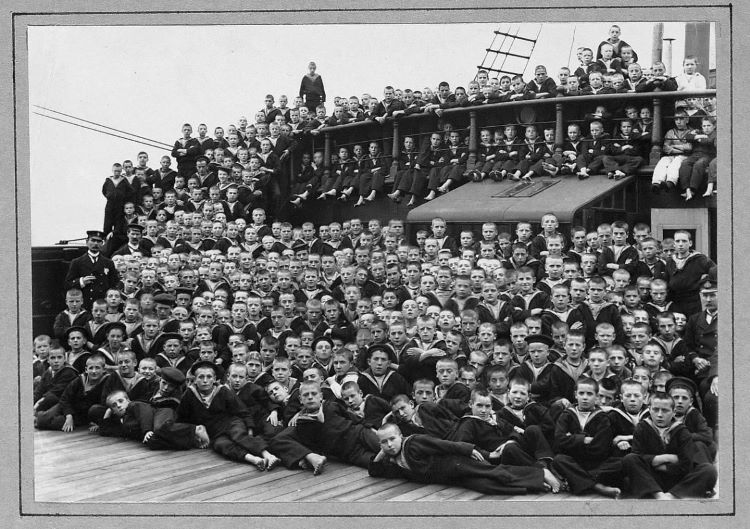

The ship filled its places rapidly. Originally fitted for 300 boys, that number was soon increased to 400. Despite its reputation as a punishment for Dundee’s ‘bad boys’, children were sent from all over Scotland and most had never committed a crime, beyond being very poor and sometimes homeless. In its early years, many came from Edinburgh. The rapid recruitment in the capital was driven by the activities of the Royal Scottish Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children, as well as missionaries. RSSPCC inspectors sought out homeless or vagrant children, who they could take to magistrate’s court for committal to industrial schools. Only a few years after the launch of the Mars, this broke out into a scandal with accusations of the agents ‘snatching’ children from the streets.

The 1894 report from the Mars revealed that, of 386 children on-board, the ship housed 45 boys under the age of 12, and 82 between 12 and 14 years old. They are described as ‘orphans, — children of criminal or drunken parents, children deserted by their parents, illegitimate offsprings of unfortunate women, in fact children who only want to be taken from bad surroundings and given a fair chance to become decent members of society’. The admissions report for 1894 shows that around half the new boys had ‘been found wandering’, that is seemingly homeless, and a third in ‘the company of Thieves, etc’.

The committee’s assessment of the advantages of the training ship revolved around its location and isolation, making note of the life in the open air, the surround river scenery, and the ‘more thorough separation of the boys from the outer world’. Under questioning about the distinction between an industrial school and a reformatory, the committee drew attention to the Mars’ own report that stated that ‘industrial school children are much the same as other school children’ and asked the ship’s agent Mr Campbell, ‘If the boys are no different from other boys why should they be sent to the ‘Mars’ to be shut up compulsorily?’, his response was ‘To take them away from their parents.’ Boys were only permitted four days at home a year if they had a ‘decent home’ to return to and requests from the family were almost always refused.

The Mars was closed down and the ship towed to Inverkeithing in June 1929 to be broken up, after sixty years as a home to boys and staff. The advent of the steam ship, and then the proliferation of destroyers, ended the demand for young boys to work aboard sailing ships. A reporter for the Dundee Courier and Advertiser collected some fond memories from local folk and staff on that day, but nothing from the boys themselves.

In this video you can find out about the history of the HMS Mars, the parallels between what happened on the ship with other moments in history and hear a poem by David Anderson.

Find out more:

Gordon Douglas, “We’ll Send Ye Tae the Mars”: The Story of Dundee’s Legendary Training Ship (Black & White Publishing, 2008).

HMS Unicorn, ‘The Sons of the Mars’. Exhibition, information available: http://www.frigateunicorn.org/on-board/exhibitions/the-sons-of-the-mars

Leisure & Culture Dundee: http://www.leisureandculturedundee.com/photopolis/mars