Every year, thousands of children and young people in the United States enter the juvenile dependency system (foster care). The term juvenile dependency refers to the process of youth in foster care becoming “dependants” of the court.

Nowadays, foster care is a system of complexity, involving a number of processes and an interconnected web of professionals, “caregivers” and a focus on the welfare of the child. However, the meaning of fostering a child in the United States has not always carried this meaning, and this meaning has evolved throughout history, as has legislation and the culture of the foster care system that exists today.

The history of foster care in the United States stretches back hundreds of years and relates back to the rule of the English over the empire’s colonies. The English Poor Laws of 1564 was imported to the United States and allowed the placement of poor children into indentured service until they became adults. It was this practice that marked the beginning of children being taken into foster homes in America.

Some 30 years after the founding of the Jamestown Colony, in 1636, seven-year-old Benjamin Eaton became the nation’s first recorded foster child.

The practice of ‘indentured’ fostering alongside placing children in jails and penitentiaries when there was no other option continued for two centuries, until 1825 when penal reformers Thomas Eddy and John Griscom organized the Society for the Prevention of Pauperism.

Its purpose was to oppose housing youth in adult jails and prisons and urge the creation of a new type of institution. This work led to the establishment of the New York House of Refuge, the first institution designed to house poor, ‘destitute’ and ‘vagrant’ youth. Within 15 years, a further 25 institutions of this kind existed across the United States.

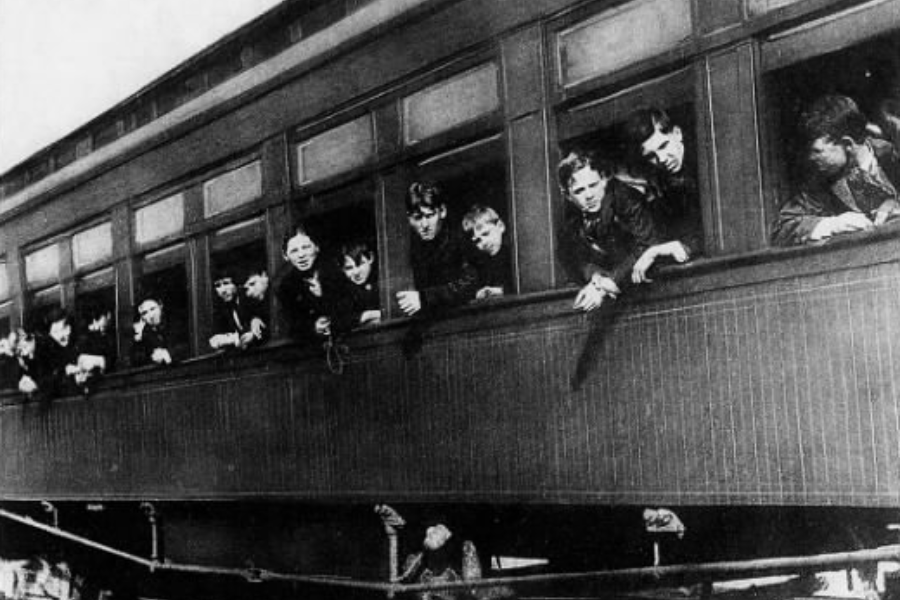

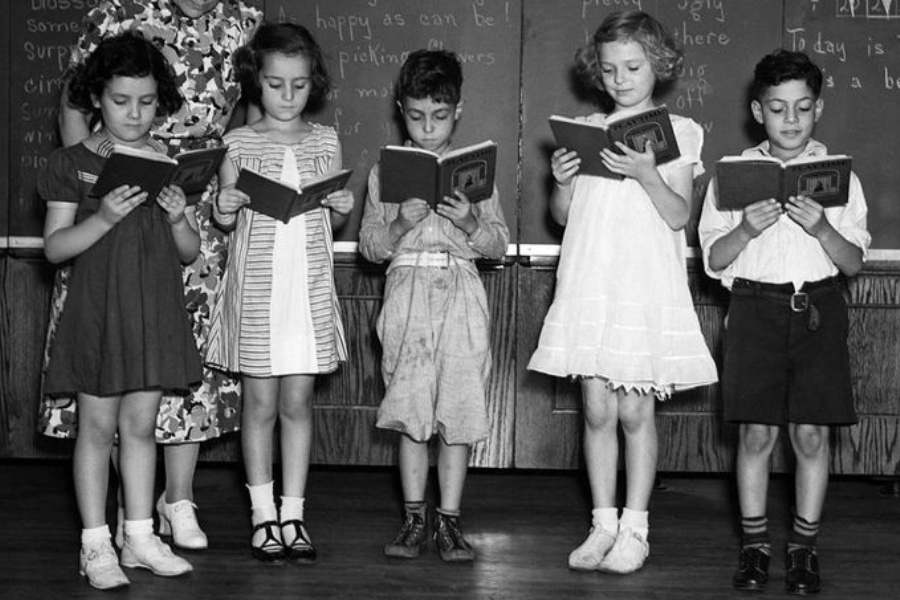

The Free Foster Home Movement was started with Charles Loring Brace, head of the Children’s Aid Society in 1853. In New York, Brace founded the Children’s Aid New York programme, which created industrial schools and provided housing, food, fresh air programs, and schooling to thousands of orphaned children. These societies pioneered the ‘Orphan Train’ movement, whereby children were advertised to families in the South and West looking to give a child a free home, usually for the purposes of manual labour. Approximately 200,000 children from cities like New York and Boston were transported via train to the American South and West between 1854 and 1929, when the practice came to an end. Children’s Aid Societies and the Orphan Train movement reflected a belief held by ‘child savers’ that by removing children from urban poverty and placing them with new families in places thousands of miles away, they would have better futures.

This belief was also reflected in the treatment of Native American children, many of whom were removed from their families and tribes, placed in boarding schools, and stripped of their culture as a means of forced assimilation. Boarding schools forbid Native American children from using their own languages and names, were given new Anglo-American names, clothes, and haircuts, and told they must abandon their way of life because it was inferior to white people’s.

By the 1900s, America’s state and federal courts had validated the authority of the state to step in and remove children from their homes to respond to abuse and neglect under the parens patriae doctrine. The first White House Conference on the Care of Dependent Children occurred in 1909 and by 1912, the U.S. Children’s Bureau was established.

In 1935 the Social Security Act was passed, leading to the United States federal government approving the first federal grants for child welfare services following state inspections of foster homes. The Court Appointed Special Advocate (CASA) model was introduced in 1977, followed by the enactment of the Adoption Assistance and Child Welfare Act in 1980, which solidified the structure for federal funding for child welfare systems and services and assured the involvement of the courts in overseeing the foster care system that exists today.

Stories

The ‘Monster’ Study

In 1939, in Davenport, Iowa, 22 orphaned children were part of an expirement on stuttering. Conducted by Wendell Johnson at the University of Iowa, with the support of graduate student Mary Tudor, it has since been described as one of the most unethical studies conducted. This was because half of the children received positive speech therapy and the other half negative speech therapy. On top of that, Johnson and Tudor told the orphanage that they were taking the children to “just to give some advice on their speech.”

The study was terminated after 5 months and no report was ever published. Despite this, many of the children had lifelong negative implications for taking part in the study. In 2007, six of these children were paid $925,000 as compensation for the damage done in the study and an apology from Iowa State University was published.

St Joseph’s Catholic Orphanage

From 1854 to 1974, St. Joseph’s Catholic Orphanage was in operation in Burlington, Vermont. During that time it was home to hundreds of children of all ages. Since it’s closure around 100 former children of the home have filed laws suits against the organisation and in 2018, following a 4 year investigation, BuzzFeed News published a report exposing the many crimes which took place in the orphanage while it was in operation. This included murder and abuse of the children in their care.

However, no charges were ever brought against the orphanage due to the statute of limitations. In December 2020 a nearly 300-page report describing the allegations, investigation, and the St. Joseph’s Orphanage Restorative Inquiry was released.