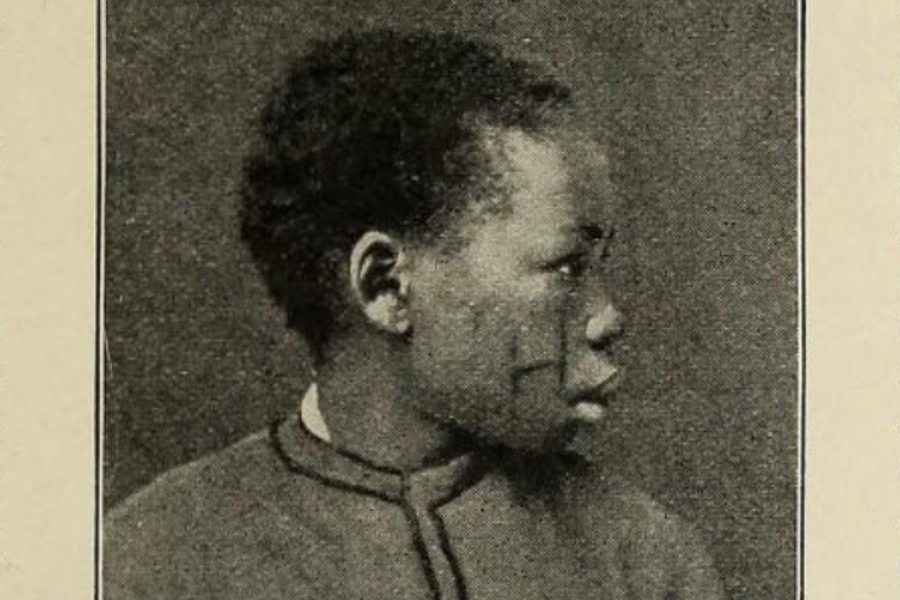

In 1879, six-year-old Suleiman Capsune was brought from Darfur in the Sudan to Britain by Robert William Felkin, a graduate of Edinburgh University. Felkin left him in the care of his sister in Wolverhampton, along with another boy named Ali Mahoom, where he attended Denstone College. Eventually the Felkins sent Suleiman back to North Africa, to an orphanage at the Assiout Mission in Egypt. Sadly, he died at only 17 years old, in 1890, which was noted in The Anti-Slavery Reporter. This is his story.

Suleiman Capsune was one of many African children, described as “rescued” from slavery, who were brought to Britain in the late 19th century. In most of these cases, the children had been purchased and freed. Some were described as orphans, though they may have had living parents or family. While there were no formal procedures for adoption, they were brought to Britain as the informal “wards” or foster children of missionaries, colonial officials or military officers. They often worked for their guardians, as translators, guides, and domestic servants.

In Capsune’s case, he was caught up in the political conflict between Darfur, Egypt and British interests. After the nominally-independent Egyptian government declared bankruptcy in 1876, Al-Zubayr Rahma Mansur Pasha, a governor in Sudan, planned an insurrection to shake off Egyptian influence. General Charles Gordon, the veteran British Army officer stationed in Egypt, intervened to put down this rebellion and, in the process, one of his medical officers became Suleiman’s guardian.

Suleiman was born in a village in Darfur, about fifteen miles south-west of Dara, the regional hub. He later described it to Felkin as a “land of running waters and trees and flowers” and he lived there with his father, mother and three older brothers. His father was a farmer who kept cows and sheep and grew cotton which he wove into cloth. When Suleiman was very young, his father gave him a small white goat to keep as a pet. Growing political instability in the region, partly due to Egypt’s economic collapse, led to an increase in conflict and in one of many attacks on his home village, Suleiman was captured by Dongolawi raiders and his father and brothers were killed.

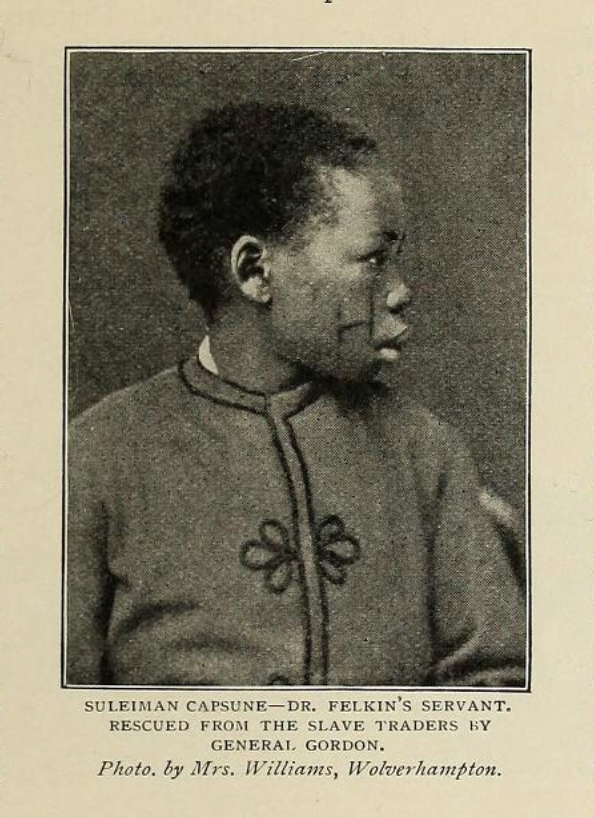

More than once, Capsune tried to escape but he was recaptured each time. His enslavers marked his face, a kind of brand that Felkin would later describe as “slave’s marks”. These caused him great distress in later life, as a permanent reminder of this trauma. At some point in the journey, General Gordon encountered the party and ordered that the enslaved people be given food and water and allowed to rest in the shade. However, he did not free them. Instead Suleiman and the others were taken to Fascher and sold. An Austrian administrator named Slatin purchased Suleiman, but soon handed him over to Felkin. There was little to distinguish this transaction from the other forms of enslavement and trafficking suffered by Suleiman, who was terrified of Felkin, and feared that he would be killed by this British man. Fortunately, Felkin’s other servant Mahoom, another child from the Sudan was able to reassure him.

The connection between the two children deepened as they lived together with Felkin’s sister, Marie Rosalie Felkin, in Wolverhampton. Both had to learn English and adapt to a new country in an unfamiliar household. Suleiman quickly became very attached to Marie and was distraught to be sent away to boarding school. At the same time as these emotional bonds formed and the Felkins paid for Capsune’s education, he was still listed as a “servant” in the 1881 census.

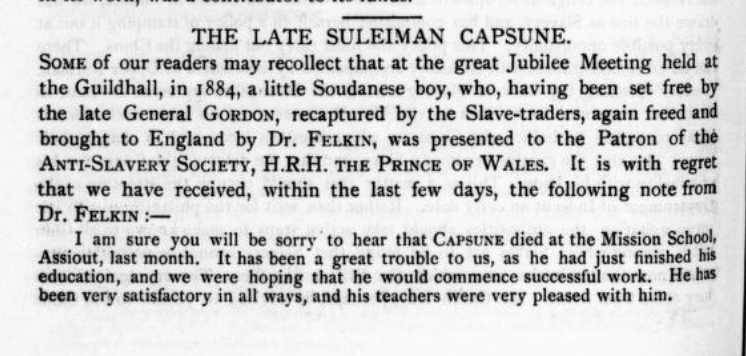

He also worked for the Felkins in other ways. Both he and Mahoom raised funds for charity, sending money to the secretary of the British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society. His example was used by the society to encourage other children to donate. At the annual missionary meeting in Donington, Felkin “astonished as well as delighted the audience by appearing in his African dress, and bringing with him one of his African boys, named ‘Capsune.’” The collection at this meeting raised £2 and 5 shillings for the Church Missionary Society and in 1884 he met the Prince of Wales at the great Jubilee meeting in Guildhall. African child wards were powerful fundraising attractions.

He was also mentioned in the press reporting of a “collection of trophies, &c., belonging to General Gordon, and kindly lent by Miss Gordon, of Southampton”. This strange assortment of objects included Chinese dresses worn by Gordon, a “throne” he used throughout the Sudan, his pigtail, weapons taken from Sudanese combatants, and other symbols of military victory. The addition of Capsune in this list of objects hints at how the children were regarded as part of the “spoils” of British imperial conquest.

Suleiman also served to further Felkin’s scientific interests. He was taken to a meeting of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland in 1883, attended by the famous eugenicist Francis Galton. The account of the meeting stated that “Felkin exhibited a Darfur boy” and gave a short account of Capsune’s life. Felkin later published on the people of Darfur, clearly Capsune was an important interpreter and informant for Felkin’s research.

When Capsune was sent to Egypt, he wrote several letters to Marie Rosalie Felkin. His letters demonstrated his growing mastery of Arabic script alongside his grasp of English. His anguish at yet another removal comes through in the letters, he wrote, “I miss all my kind friends very much…” and could not “help crying”. In each letter he gave salaam, not only to Felkin, but also to friends and neighbours. His early death came not long after.

The correspondence from and about Suleiman Capsune gives us a much clearer picture of his life story than that of many other African child wards and foster children of the 19th century. The letters tell us that he occupied many roles: servant, adopted child, scientific collaborator, and fundraiser. As an orphan swept up into the rapid expansion of British power in North Africa, he sought to find new connections with friends and community. His letters tell us that he was not just a pawn in colonial politics, but a boy seeking to find a new place for himself.

Sources:

- British Library, Gordon Papers

- British Library, Newspaper Archive

- Robert William Felkin, Uganda and the Egyptian Soudan (London: S. Low, Marston, Searle, & Rivington, 1882).

- Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, Volume 12, 1883.

- The Anti-Slavery Reporter, Volume 3, number 6, 1883.